When installing some non-pip installed packages, especially in the deep learning field, we may use python setup.py build install to build the packages locally. Then, some typical problems may happen in this stage. An CUDA mismatch error may be:

This error can be caused for many reasons. I just report my situation and how do I solve it.

Why this happen?

Some packages need to be compiled by the local CUDA compilers and to be installed locally. Then, those packages cooperate with the pytorch in the conda environment. Therefore, they need to be a compiled with the same version (at least same major version, like cuda 11.x) CUDA compilers.

- First, we inspect the conda environment’s pytorch’s CUDA version by:

1 | import torch |

This means that our pytorch is compiled by cuda 11.3. (Same as the error message above!)

- Then, we inspect the system’s CUDA compiler version by:

1 | nvcc -V |

This means that our system’s current CUDA version is 10.2. (Same as the error message above!)

Therefore, the compiler version going to compile the package is NOT consistent with the compiler compiled pytorch. The Error is reported.

How to solve it?

So to solve this problem, the easiest way is to install a new CUDA with corresponding version. (In my test, I don’t need to install an exact 11.3 version, only an 11.1 version is OK)

- Install the CUDA with specific version. Many installation tutorials can be found online (skipped)

- Export the new path in

~/.bashrc: Add following command at the end of~/.bashrc:

1 | export PATH=/usr/local/cuda-<YOUR VERSION>/bin:$PATH |

(Remember to change <YOUR VERSION> above to your CUDA version!!)

- Open a new terminal, type in:

1 | nvcc -V |

- Then it should work! Go to the installation directory, and then switch to the target conda environment, and install!

Common techniques for debugging

- Inspecting the pytorch’s CUDA version:

1 | import torch |

- Inspecting the system’s CUDA compiler version:

1 | nvcc -V |

or

1 | from torch.utils.cpp_extension import CUDA_HOME |

- Change the

$PATHvariable, so the new CUDA can be found:

Add following command at the end of ~/.bashrc:

1 | export PATH=/usr/local/cuda-11.1/bin:$PATH |

REMEMBER to change the CUDA version to your version.

- Delete the cached installing data

In some situation, when we modified the compiler, we shall build the package from scratch.

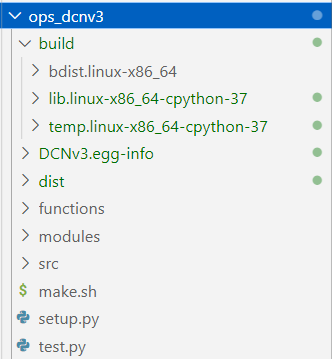

Remove any of the build, cached, dist, temp directory! E.g., the build and DCNv3.egg-info and dist directory below.

(But be careful that don’t remove the source code!!!)